Introducing Strudel

April 03, 2022

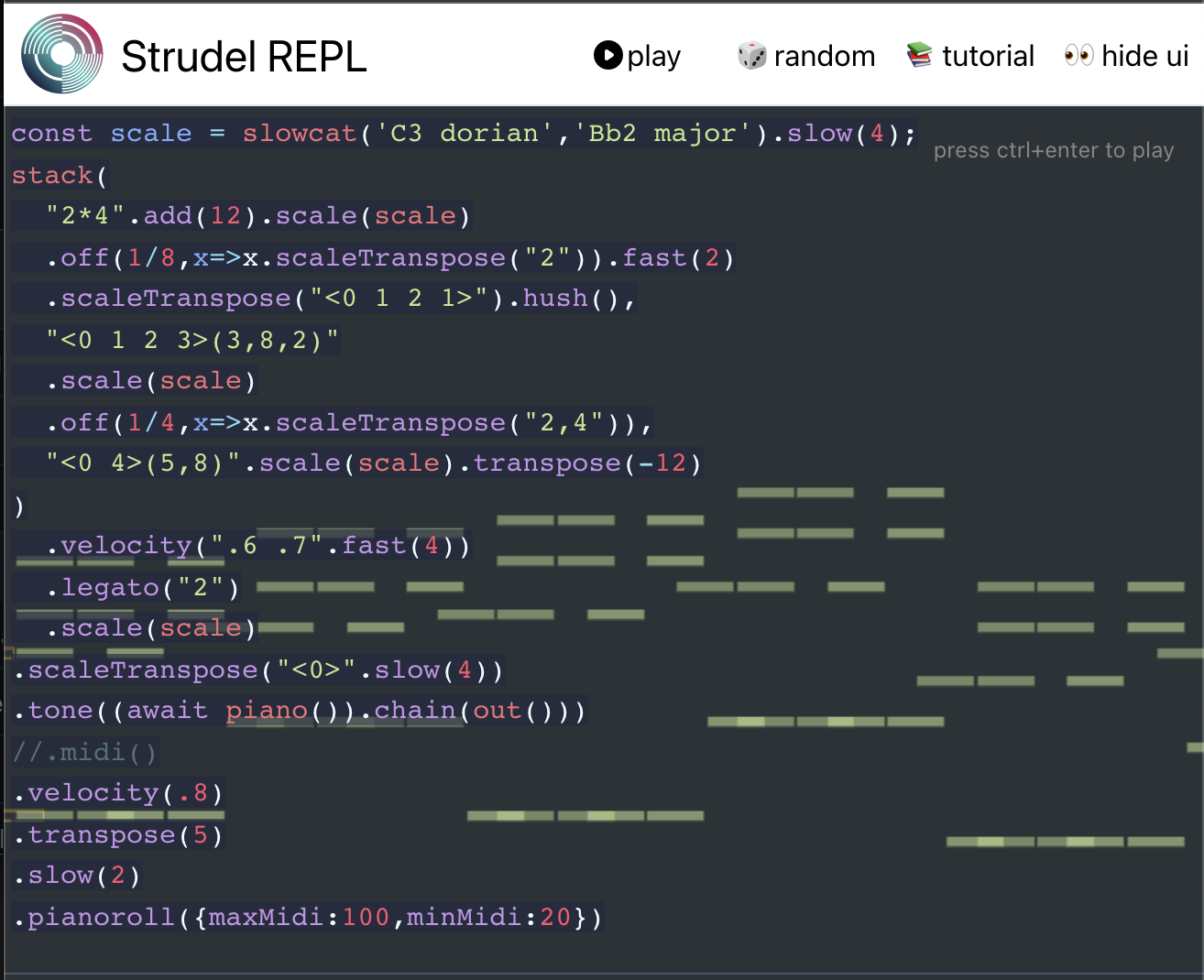

The last couple of months, I've been hacking on Strudel, which is a live coding environment that brings the ideas of Tidal Cycles to the browser:

In this post, I want to write about how it all started, and describe the general features of strudel from a technical point of view.

Table of Contents

How it started

When I wrote the post about tidal.pegjs, I already messed with tidal mini notation, with the original plan of using the mini notation as part of my rhythmical project. While working with tidal.pegjs, I had some problems with the event querying, so I filed an issue.

There, I came into contact with yaxu, the creator of Tidal Cycles. He had already started to port tidal's patterns to Javascript under the name of strudel. This "port" originated in a rewrite of tidal (remake), which was ported to python (vortex), and then ported again to JavaScript.

I was highly interested in using strudel as part of my own endeavor to write dynamic music pieces. So far the Tidal Discord Server was the main communication channel in the development of strudel, and we had many fruitful discussions. I thought it would be a good idea to have a REPL, where strudel patterns can be entered and played back. After some weeks of pretty active collaboration, we were able to develop a pretty amazing live coding environment.

About the REPL

My main focus at strudel was the REPL (Read + Evaluate + Play + Loop), which allows playing and editing strudel patterns in real time, inside the browser. The basic flow looks like this:

- Read: Edit a strudel pattern in the code editor

- Evaluate: Run it to create a pattern instance

- Play: Listen to the patterns output

- Loop: Go back to 1

There is also a Mini REPL, which can be used to play strudel patterns inside the tutorial, or as part of this post.

About Patterns

Let's talk about the basic entity of strudel (and tidal): Patterns. A Pattern basically translates a timespan into a set of events:

const pattern = sequence('a', ['b', 'c']); // create pattern

const events = pattern.querySpan(0, 1);

// const events = pattern.firstCycle();

const readable = events.map((e) => e.showWholes());

console.log(readable);

This is what happens here:

- We create a pattern, using

sequence, which is one of many ways to create a pattern. - We query the pattern from

0to1. Those numbers are units of time, called cycles. - We convert the queried events to a readable format

The following output will be logged:

(0/1 -> 1/2, a)

(1/2 -> 3/4, b)

(3/4 -> 1, c)

Each line represents one event, showing the start and end time, followed by the value.

That list of events could now be given to any type of scheduler to play them back. Example:

Here, we only need to write down the pattern itself, and the strudel player will handle the rest. Internally, it will repeatedly query the pattern and play back the generated events. The pattern can also be edited and updated while it is playing!

Pattern factories

In our example, sequence is a function that creates a pattern, which I also like to call pattern factories. Each pattern factory will treat the flow of time differently.

sequence

In a sequence, elements are played one after the other, and each element is divided equally over the whole time. A sequence also supports nested groups, using arrays. Each array acts as one element, and the contents of the array are treated as a nested sequence.

In our example ['b', 'c'] is a nested sequence. The array itself takes 1/2 of the whole sequence, while each element inside takes 1/2 of the array. So each element of the array takes 1/4 of the whole sequence.

a = 1 / 2;

b = ((1 / 2) * 1) / 2 = 1 / 4

c = ((1 / 2) * 1) / 2 = 1 / 4

This behaviour is equivalent to how sequential works in rhythmical, as I've already described in much detail in my post about rhythmical trees.

stack

Another way to create a pattern is stack. In a stack, each element is arranged in parallel:

const pattern = stack('a', 'b', 'c');

// querying is the same as above

This is the output:

(0/1 -> 1, a)

(0/1 -> 1, b)

(0/1 -> 1, c)

Here, all elements have the timespan, as they are parallel.

This is equivalent to the parallel node in rhythmical.

more

There are many more pattern factories. Without going too much into detail, here's a sneek peek:

pure(element): repeats the given element inside one cycleslowcat(...elements): each element takes one cycle (short = cat)fastcat(...elements)/cat: element are divided over cycle (short = seq)timeCat(...[weight, element]): like fastcat, but the duration of each element is determined by its weight

To find out more, check out the Strudel Tutorial

Pattern modifiers

Each pattern can be modified to change it's behaviour.

fast / slow

With fast and slow, the playback speed of a pattern can be controlled.

With .fast(2), the pattern will be twice as fast. Contrary to fast, slow will do the opposite:

add / sub

With add and sub, we can add or subtract numbers. Using it with notes will transpose them:

more

There are MANY more pattern modifier methods. A little taste:

- early / late: move pattern backwards and forwards in time

- rev: reverse playback order

- mul / div: multiply and subtract

- struct: change temporal structure

- echo: repetition effect

To find out more, check out the Strudel Tutorial

Patterns as Inputs

One of the most interesting features of tidal is that you can use patterns itself as inputs to pattern methods! The above snippet can also be written like this:

Instead of passing a primitive number to add, we pass a pattern of numbers!

This will call the add function with a different number each cycle, adding the current number to the sequence.

Most of strudel's pattern methods can be patternified!

Mini Notation

Another handy feature of Tidal is the mini notation. It is an alternative, more compact way to express patterns, using a domain specific language. The last snippet can be minified like this:

Mini notation only supports a subset of pattern functions:

| mini notation syntax | function syntax |

|---|---|

c3 e3 |

sequence(c3, e3) |

c3 [e3 g3] |

sequence(c3, [e3, g3]) |

c3,e3 |

stack(c3, e3) |

<c3 e3> |

slowcat(c3, e3) |

c3\*2 |

stack(c3, e3).fast(2) |

c3/2 |

stack(c3, e3).slow(2) |

c3(3, 8) |

pure(c3).euclid(3, 8) |

c3@3 e3 |

timeCat([3, c3], [1, e3]) |

~ |

silence |

You can write entire "songs" in mini notation:

As always, to find out more, check out the Strudel Tutorial

About the mini parser

The mini notation parser comes from a project called krill, which contains a peg.js grammar that turns mini notation into an AST. By walking over the AST nodes, a pattern can be constructed. I decided against using tidal.pegjs, as the krill parser had more features and the AST was easier to process.

If we parse the following mini notation:

'c3 [e3 g3*2]';

... we get this ast:

{

"type_": "pattern",

"arguments_": {

"alignment": "h"

},

"source_": [

{

"type_": "element",

"source_": "c3"

},

{

"type_": "element",

"source_": {

"type_": "pattern",

"arguments_": {

"alignment": "h"

},

"source_": [

{

"type_": "element",

"source_": "e3"

},

{

"type_": "element",

"source_": "g3",

"options_": {

"operator": {

"type_": "stretch",

"arguments_": {

"amount": "1/2"

}

}

}

}

]

}

}

]

}

To get a pattern from the AST, we can walk over all nodes, and construct the following call:

sequence('c3', ['e3', pure('g3').fast(2)]);

I won't go into the implementation details here, but it's essentially just a recursive node walker. If you're curious, you can read the source here.

Why the mini notation works

If you know JavaScript, you might be confused by the fact that we call .add on a string, which normally does not exist.

In the REPL, there is a little convention:

Use double quotes for mini notation, use single quotes for strings

With this convention, mixing mini notation and regular function calls is much easier.

Note: This convention will only work if the input code is transpiled using some AST magic!

Syntax Sugar

The mini notation, and other forms of syntax sugar are possible thanks to shift-ast.

Check out my little post about shift for more info on that.

Before the user code is evaluated, it is transpiled using shift-ast. This allows hacking JavaScript to a greater extent.

Double Quotes

To make the mini notation work, strings with double quotes are converted to mini function calls:

Pseudo Variables

Variables that have note format are rewritten to strings:

Operator Overloading

In regular JS, overloading operators is not possible. With shift, it's trivial. This allows rewriting multiplications to fast calls:

So far, just multiplications and divisions are overloaded, but there are much more planned in the future.

Source Locations

This is not really syntax sugar, but also a transpilation handled by shift. It allows passing source location information to the pattern:

Using those locations, we can display the current event in the editor!

Evolving Patterns

If you look at the examples so far, you might know wonder why we have to query again and again as time progresses. For simple repeating patterns, this might not be necessary, but the amazing property of tidal patterns is that they can evolve over time! This allows creating less repretitive music.

Signals

One way to make patterns more dynamic is using signals. Signals are continuous and will be "sampled" for events that use them:

So far, there are sin, cos, tri and saw. More will be added in the future.

I found signals especially useful to control note length (.legato) and velocity (.velocity).

Irrational Numbers

To make a pattern more irregular, irrational numbers can be used:

Scheduling

After understanding the many facets of patterns, let's talk about how to actually generate music from them.

Scheduling with Tone.js

Until now, the event scheduling in the REPL is based on the Tone.js Transport. This is a stripped down version of the scheduler:

const activeCycle = Math.floor(Tone.getTransport().seconds / cycleDuration);

const query = (cycle = activeCycle()) => {

Tone.getTransport().schedule(() => query(cycle + 1), cycle + 0.5);

pattern.query(cycle, cycle + 1).forEach((e) => {

/* play event... */

});

};

In essence, we have a function that calls itself in the future. You can read the full code here. While the scheduling with Tone.js works, I wanted to implement a simpler scheduling system that doesn't depend on Tone.js.

Scheduling with the Web Audio API

I already have a solution that works, but I have not yet integrated it in the REPL. The solution is based on the

Tale of two clocks, which is the de facto standard of Web Audio Scheduling.

Basically, a setInterval loop runs in a web worker. On each callback, the worker will emit a tick message, in which

the next time span is calculated:

this.worker.onmessage = (e) => {

if (e.data === 'tick') {

const begin = this.lastEnd || this.audioContext.currentTime;

const end = this.audioContext.currentTime + this.interval;

this.lastEnd = end;

this.pattern.query(begin, end).forEach((e) => {

/* play event... */

});

}

};

The above snippet is simplified for didactic reasons. In the actual implementation, I seperated the worker from the scheduler.

Playback

In the Strudel REPL there are multiple ways to play back events:

Playback with Tone.js

The first way to play events was using Tone.js instruments, via .tone:

As constructing Tone Instruments is rather verbose, I added some helper functions:

Behind the scenes, the .tone method will define a onTrigger function on each event.

When the scheduler plays the event, it will just call that function.

While Tone.js is really comprehensive, I experienced some performance problems with it. It seems like some Tone.js instruments or effects suffer from memory leaks, which results in a large amount of garbage being created. Depending on the complexity of the song, this will sooner or later result in cracks and crashes.

Playback with MIDI

It was a matter of copy pasting code from my previous post about MIDI in JS to get MIDI output working. Midi is currently not supported by the mini repl used here, but you can open the midi example in the repl.

Playback with OSC

The original tidal uses OSC messages to talk to Super Collider, which runs Super Dirt. Though sending OSC messages via WebSockets is possible in the browser, Super Collider does not support it yet. But we were able to make it work by running a local node server that forwards Websocket messages to Super Collider via UDP. This feature is still a work in progress, but it will be available on the REPL soon.

Playback with the Web Audio API

While experimenting with the scheduling, I also wanted to try playing events with bare Web Audio nodes, to keep Tone.js out of the picture completely. Like the scheduler, this is not yet part of the REPL, but you can already play with it here.

The great advantage over Tone.js is that everything can be created dynamically, allowing sound params itself to be patterned. So for each event, we can create a new audio node. I tried the same with Tone.js, but it will break down quickly. It's something that is not intended by design.

Strudel Packages

After an initial hacking phase, I split up strudel into multiple npm packages:

- @strudel.cycles/core

- @strudel.cycles/eval

- @strudel.cycles/mini

- @strudel.cycles/midi

- @strudel.cycles/midi

- @strudel.cycles/tonal

- @strudel.cycles/tonal

- @strudel.cycles/tone

- @strudel.cycles/xen

In this post, I've scratched the surface of most of those, except tonal and xen, which will be the topic of a future post.

Strudel in Action

I was happy to take part on the 10th birthday of Algorave, using Strudel for a 10 minute live coding performance:

In this stream, I used Strudel to emit MIDI messages to different synths + drums on different midi channels.

Check out the Eulerroom Youtube Channel for all the other performances!

The Future of Rhythmical

rhythmical is dead, long live strudel!

So far, I've written many posts about rhythmical, which was my attempt to create a dynamic music sequencer. I am now certain that I will stop developing it and shift my attention to Strudel, as it has proven to be much more powerful. In retrospect, it seems almost dumb to have chosen JSON as the primary "language", as it's pretty limited. Nevertheless, rhythmical was an important stepping stone for me to get into music coding. Based on the experience with it, I could reuse some implementation ideas, which sped up the development. I even ported some tunes from the rhythmical REPL.

Conclusion

This post was an overview of what happened so far in the development of Strudel and it will definetly not be the last. I am very happy how Strudel evolved so far, and I like the fact that I am not alone hacking in a vacuum! Thanks to all the people involved, especially yaxu for writing the core logic, distilling his years of experience with tidal.